A week ago, a friend and I made the trip from Philadelphia to Carlisle, PA to visit the site of the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School, now the Carlisle Barracks and a current U.S. Military installation. As the descendant of someone who attended a residential school (Haskell, in Kansas, but more on that later) I was interested in learning about perhaps the best known of the residential schools. Reading about it wasn’t enough, especially when there was little information on how the spatiality of Carlisle impacted its Indigenous boarders.

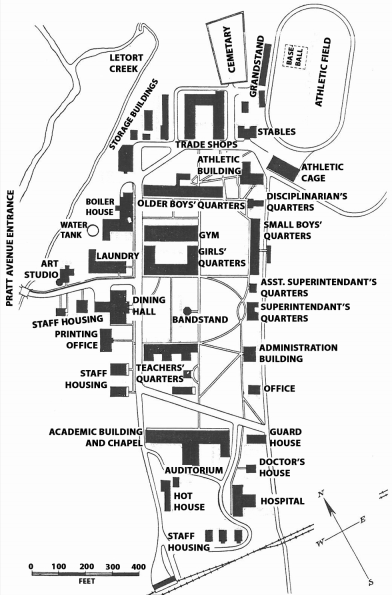

There was limited information online about visiting, but it was relatively easy to make it to the security checkpoint and get visitor passes to enter the base. We were provided with a map of relevant sites and small descriptions of each.

There is a small museum onsite, located in the Hessian Powder Magazine. The exhibit explains how the site came to be, detailing Revolutionary War histories and extensive military influence. Eventually, due to orders from the US Secretary of War, Carlisle Barracks became the first Indian Industrial School in the nation. The Hessian Powder Magazine became a guardhouse for the school. The Magazine Museum also elects to share a series of 20th century events, including a list of notable sporting victories. Notable alumni include athletes Jim Thorpe (Sac and Fox) and William Henry Dietz, and Charles Bender (White Earth Band).

The remaining buildings onsite are not as visitor-oriented. The gym, which has since been named Thorpe Hall (after Jim Thorpe) retains much of the original character seen in the sporting photos, but it is noticeably modernized; similarly, other places retain a semblance of their past selves, but time has imposed many notable changes on the former school grounds. It didn’t feel like the school, in fact I would generously suggest that it seemed, at best, like an empty college campus with a striking amount of military personnel. Indeed, it is a military base now, just as it had been before the school.

The history is obvious to those who are paying attention. There is still a statue of Jim Thorpe, an “Indian Art” studio, and signs labeling School Road and Indian Garden Lane. And then there is the cemetery.

There are 227 or so graves onsite, many of which are for persons unknown. When known, the deceased are marked with their name and tribe. Seeing as the graves are for school-age children, visiting the cemetery is heartbreaking, especially knowing that the students (some of whom were from hundreds, thousands of miles away) were so far from home at the time of their passing. They may not have been at school voluntarily.

Architectures of Genocide

Needless to say, the Carlisle Barracks are not Indigenous architecture; they are colonial in nature and resemble, oddly enough, a variety of styles more remniscent of the American South than rural Pennsylvania. A visitor might imagine, just from an image, that they were in Alabama rather than a mid-Atlantic state.

For Indigenous students attending school there in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, I might imagine that the environment would feel incredibly rigid and foreign, perhaps even stifling. I believe this is more closely related to the militaristic nature of the space, which is deeply tied to the colonial intentions of the school. A military installation is a very fitting spot for the genocidal mission of the school, commonly described as “Kill the Indian […] and save the man.”1

While “genocide” is a contested term when used with regard to the Native American expulsion and integration that took place under American rule, it is certainly appropriate considering the intent and extent of the damage done to Indigenous groups across the continent. Author Benjamin Madley discusses the effects on Indigenous groups in California following the Gold Rush2 and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz has elaborated on these histories extensively in the chapter “The United States Did Not Have a Policy of Genocide.”3 As such, the academic consensus on this issue appears relatively simple: the UN definition of genocide is as follows:

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

The UN also posits that the above definition is functionally too narrow, asserting that genocide includes two components, both mental and physical, with the physical including the above five parts. The mental component is defined simply as “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.”

If we look at residential schools, and at Carlisle, as a functional part of an organized effort to harm or completely destroy Native American cultures and societies, then we examine the Carlisle Barracks as a landscape of genocide. Then it makes sense why Carlisle doesn’t look like a place for Native American students, resisting any suggestion of reflecting Indigenous culture or values—it was never interested in doing so. It was established as a place to kill the “Indians” who went there, assimilating them as “men,” as opposed to “savages.”

I could go on about the rigidity of the plan, about the distance of the buildings and European influence of the architecture, but all of that can be argued not from the perspective of the school but from the intent of a military installation. I will skip these musings and simply state my belief that “school” is an inappropriate term for the spatial experience of Carlisle, just as it is a term used to obscure the ill-intended consequences meant for “students” who attended. You will see this, and feel it, if you visit.

Final Thoughts

This is a first post on residential schools, Native American spaces, and architectures of genocide. I hope to explore these ideas further and interrogate them with greater clarity in the future.

Citations, further reading, and more information:

1National Conference of Charities and Correction (U.S.). Session. Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities And Correction, At the … Annual Session Held In … Boston: Press of Geo. H. Ellis, 1916. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89030648919

2Madley, Benjamin. An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. Yale University Press, 2017.

3Gilio-Whitaker, Dina, and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. “All the Real Indians Died Off”: And 20 Other Myths About Native Americans. Beacon Press, 2016.

4“Genocide.” United Nations, United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the responsibility to protect, http://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/genocide.shtml. Accessed 20 July 2024.

Leave a comment