My most recent trip to Washington DC naturally included a trip to the Museum of the American Indian. I had plenty of thoughts.

I’m an Indian, as in the Name

Am I? I personally never thought so. I take issue with the word order. An American Indian suggests that I’m fundamentally an Indian, just an American one. I object to that. Being called a Native American says I’m an American, and I’m a native one. That’s more accurate to how I feel.

Then again the descriptor is not meant to match my ethnic identity. The federal government classifies us—-for legal reasons—- not as an ethnic group but as a political identity.1

The Native Architecture

The museum is a direct statement on Indigenous design, being the most conspicuous “Native building” nationally. It also has the unique challenge of representing all American Indians. The design was completed by Douglas Cardinal (Blackfoot).

I’m a personal fan of Douglas Cardinal’s approach to the museum. I think it’s fantastic. The flowing, curvilinear form is a fascinating juxtaposition to the overwhelming neoclassicism in Washington DC, and since it’s deeply related to the circle (read: talking circle, medicine wheel, cyclical thinking) it is perhaps the most subtle hint towards commonly held Indigenous beliefs and thinking. But it’s not overbearing.

I appreciated reading Cardinal‘s discussion of his design for the Canadian Museum of Civilization, as I think it’s related to his work for the MIA:

“Symbols are the way we communicate. Words and sounds are symbols and writings are symbols of words and sounds. Pictures are symbols of feelings, events, and can communicate impressions beyond words in two dimensions. Sculpture goes beyond pictures to symbolize impressions. Architecture, perceived as living sculpture, symbolizes even more the goals and aspirations of our culture. My challenge is to evoke images, creating images in sculptural and architectural forms that symbolize the goals and aspirations of this National Museum.”

…

“Within this great continent, wherein lies this expansive and diverse nation, I could sense the feeling of time, the rhythm of time and the way nature had shaped and formed the land – that the formations had been carved by the elements and forces of nature, by wind, rain, the movement of water, the warmth of day, the coolness of night, the seasons. I felt that the building itself should express the evolution of the natural formations.”

I do think Cardinal’s building reads in accordance with his mission to design with the elements. The exterior reads as a natural formation, albeit obviously intentional. There is indeed a rhythm to the sculpture of it all, an undulating beat as the building flows in and out. There are no hard edges; there is a break from rigidity and rectilinearity. The inside flows from the entry courtyard as if it were a continuation of the outside, minus the security checkpoint. The central atrium draws visitors upward, into the sky.

I would be excited to visit more Cardinal projects to see how this strategy compares.

The Museum as a Challenge to the Capitol

I did enjoy the museum’s location on the national mall. It lies a mere block away from Capitol grounds, and of the history museums on the mall, it has perhaps the most (challenged only by the National Museum of African American History) to say in response to the American government. Namely, that centuries of American policy have wreaked havoc on Indigenous peoples and their nations.

The interior is divided into four floors, with exhibits on Native American military service (we have the highest rates of any one ethnic group)2 to the many treaties with the American government which have since been broken. Apparently, the museum has so many treaties to display that they have to rotate them every six months or so.3 The third floor alone is divided into an exhibit discussing the Battle of Little Bighorn, Indian Removal/the Trail of Tears, and Pocahontas. Several things haunt me:

- The Battle of Little Bighorn was a Native success followed by a crushing defeat. Native victors were hailed as celebrities following their victory. The artistic depictions of the battle are eerie.

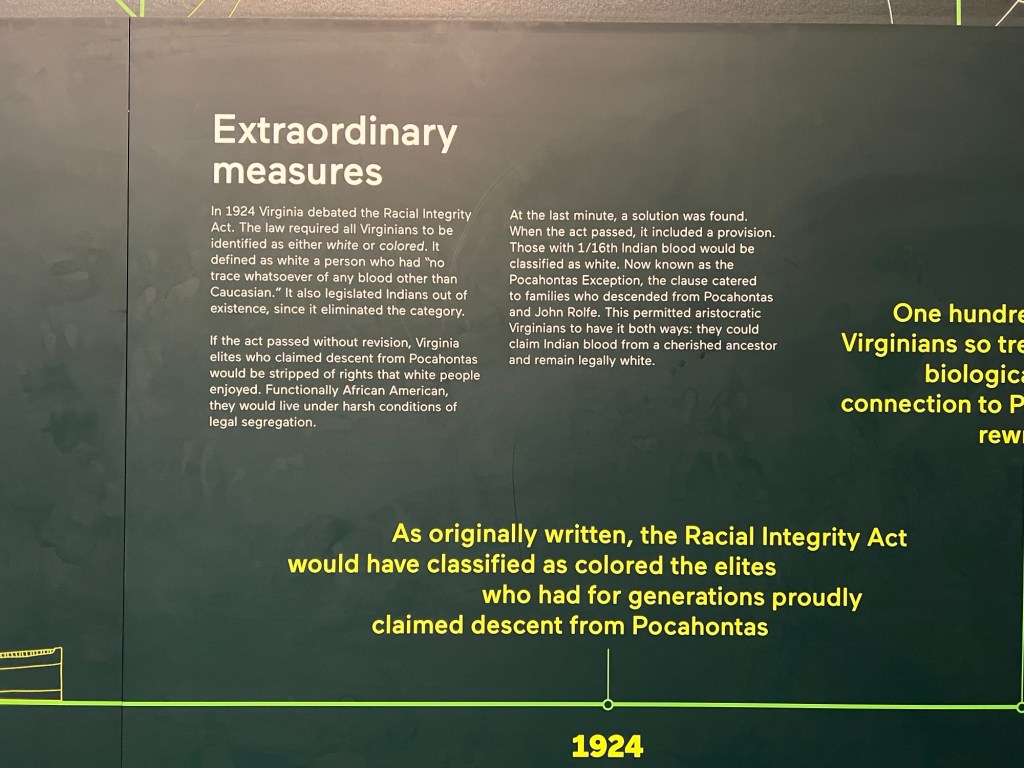

- The Pocahontas Exception. Virginia lawmakers were so desperate to claim native heritage while not being labeled as Black that they created a legal exception for those of 1/16 heritage or less. Under Virginia race laws, I would be Black, but any yahoo claiming false relation to Pocahontas could be white.4

- There were many notable voices that spoke out in opposition to the Removal. Andrew Jackson didn’t care; he stood to gain from removal as he had invested in the land that the federal government would snatch.5

- The dispossession of the Five Tribes through Indian Removal is what paved the way for the cotton explosion of the south. The land that had once belonged to Indigenous nations was then exploited for cash crop growth, namely cotton, then allowing slavery to boom. In this way, evil led to more evil, and dispossession was one of the dominoes that fell on the nation’s path to civil war. This is perhaps the most haunting legacy.

The museum explores all of these topics in depth with language that doesn’t relent from its condemnation of the depravity that took place. To walk out into modern-day Washington DC, just steps away from where some of the legislation that so deeply affected Native peoples was originally written, is an odd experience. There is certainly a part of me that won’t really forgive history for how this all played out.

Another thought crossed my mind: it’s a shame the museum couldn’t have been dedicated to art or politics or history, especially considering the unique cultures and governments that exist across the myriad Indigenous groups on the continent. But instead, we have to talk about displacement. There is seemingly little room for conversation after one attempts to broach the topic of displacement—it sucks all the air out of the room. There is little space for the much-needed celebration of our achievements and diverse cultures. That is a tragedy in itself.

The Museum in the Native City

I believe that the museum is a necessity for our Native City; our shared memory is a part of us and it lives within each of us. We are all storytellers, and museums could function as a place for our cultural memories to live on. Indeed, even beyond empirical knowledge (as referenced in a previous post) our personal and relational knowledge is equally valid, and needs to be passed on.

All of this is because public memory is a part of what makes the Native City thrive. There have been so many conversations about public memory and what we choose to memorialize, ranging from iconoclasm to the destruction of Confederate monuments across the American South. Much of my personal research and writing pre-blog has been focused on the recent discussion about removal and whether or not we should be destroying statues of people who enacted change, for better or for worse.

I’m confident this will be relevant later, so my abbreviated thoughts now are that memory is important. But some things are meant to be in museums, surrounded by ample context. I believe this because I simultaneously think the things we build in the public sphere are reflective of our deepest societal values. Dark memories and things we have culturally disavowed should not be on our streets, presented as if they are legacies we wish to carry on. Disavowment necessitates removal.

Also on record: I am extremely skeptical of memorializing people. Our greatest leaders, despite often representing our strongest ideals, are always fallible. Sometimes statues of people can suggest that we agree with their idea as well as their faults. This is incredibly dangerous. Sometimes our ideals are better represented and remembered in the abstract, without being tainted by the tangible actions of humans themselves.

All of this said, I’m interested in how we create museums in the Native City. Is the Native City a museum itself—a living museum? With every memory a potential political statement, how do we choose what we remember and what we continue to celebrate? How often do we choose to forget? And when, if ever, do we reach peace with horrible histories?

References

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-the-federal-government-needs-to-change-how-it-collects-data-on-native-americans/

- According to the museum, one in every four eligible Native Americans served in the Vietnam war. The reasons for this range from the draft, patriotism, and desperation. The effects of it can still be felt in powwow grand entries today, with emphasis placed on Native American warrior culture and respect for veterans and public service. Go to any powwow to see this in practice.

- This was noted during our visit. According to the museum website, rotation happens “every few months.” https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2017/11/02/nation-to-nation-treaties-at-the-national-museum-of-the-american-indian/

- The Pocahontas Exception: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/racial-integrity-act.htm#:~:text=This%20became%20known%20as%20the,nullifying%20their%20white%20racial%20identity.

- Jackson made off with 45,000 acres of southern land. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/07/andrew-jackson-made-a-killing-in-real-estate-119727/

Leave a comment