I have recently been struck by the beauty of knowing what things are called. It’s one thing to know the names of your tools; it’s a necessary part of being considered proficient in the language you speak. It’s quite another to know the names of your companions and the other living beings around you.

It has been made clear to me that I was not acquainted with the trees and animals before this year. I did not know Quercus alba (white oak) despite growing up next to White Oak Bayou. I did not know Quercus stellata (post oak) despite speaking the name often as a child. I liked sassafras but did not know Sassafras albidum, nor Hamamelis virginiana (witch hazel) nor the taste of Betula lenta (black birch).

Today I put wintergreen on my tongue and let the plant speak.

I wondered, when I did not call these plants by name, did I ever truly notice them? Did I look and attempt to draw. Did I see without judgment? Just observation?

You are sadder when a neighbor dies if you know their name. Several years ago we had to remove two big oak trees in our yard because they had gotten sick. I was sad for all the memories I had made sitting at their roots and playing in the dirt, building sand castles in the play area that lay in their shadow. But I wasn’t sad for the trees themselves. I think I would have been sadder if I had known they were oaks at the time, just because I would have known them a bit better.

People say that plants—-that nature—-speaks, and they often mean it in a semi-spiritual, mostly unserious way. But the truth is that nature does speak to someone who is familiar, someone who is careful observer.

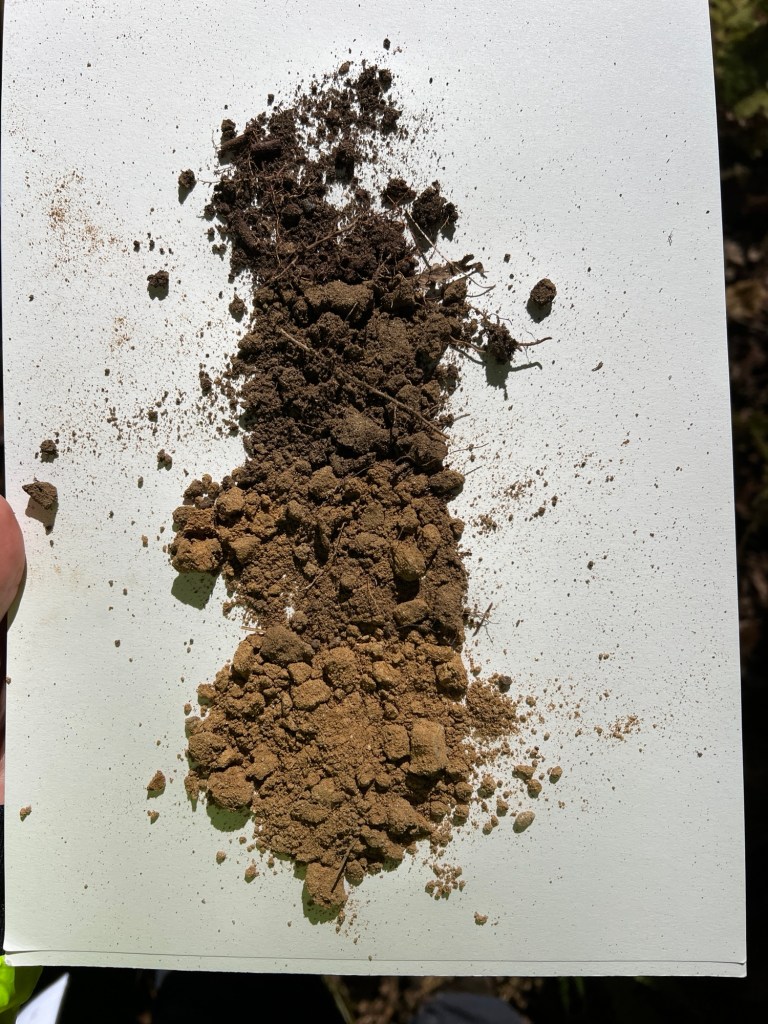

Today I went on a hike in the Serpentine Barrens in Chester County, Pennsylvania. The area has two main soil types, those of the Manor series (Micaceous schist) and the Chrome series (Serpentine). The barrens follow the Chrome series soils which are more neutral in Ph than the Manor series. While the surrounding Manor soils are good cropland and host an abundance of life, the serpentine area is stony and unfavorable for plant growth, with high levels of iron and magnesium and toxic levels of nickel, chromium, and cobalt.

Yet life thrives here, just a different kind of life, and the Blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica) as well as Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) are found in abundance. The change in plant life is telling you about the underlying geology, the geological history of an area. This ground was once the sea floor, they say, and the serpentinite was once buried under rock. All of it was, indeed, once underwater.

Likewise the heath family signals for acidic soils just like in the New Jersey pine barrens. (Side note: isn’t it sad that the resilient and hardy pitch pine was decimated both in the serpentine barrens and in large places of the pine barrens? And the Atlantic white cedar?) Similarly, stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) tells you the soil is rich. Voices are everywhere you turn your ears.

Leave a comment